What really went over best was when I dropped in a slide that connected New York to the local neighborhood of Zorrotzaurre, which only worked because I got there a day early and was able to run to the area and take pictures. You'll also note that it's tailored for the conference, and when I deliver it again, I'll make lots of changes to reflect a new audience.

Anyway, hope y'all like it. Enjoy!

New York City Graffiti Murals

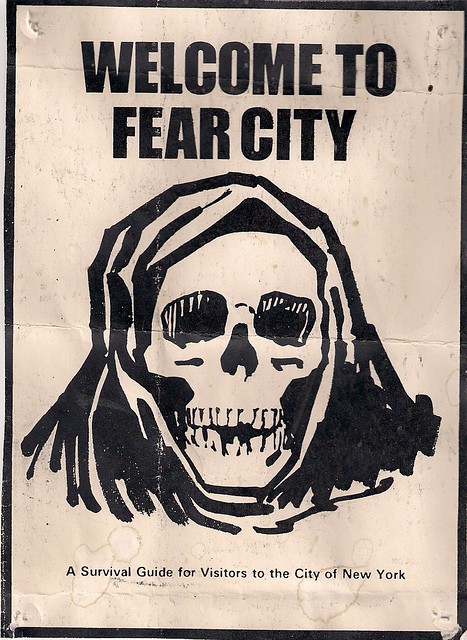

In 1975, New York City was the kind of place where the city’s police and fire unions created this “survival guide.”

They were trying to prevent layoffs at the time, and one of their strategies was to promote the fear that the city was completely out of control. Unsurprisingly, the reaction to it was so negative, it was never actually distributed, but it tells you a lot about the way things were back then.

Fast forward 40 years, and you’ll find a very different New York City from that one. The crime that was rampant back then has receded, and real estate prices have sky-rocketed. A penthouse in the One57 tower on Central Park, for instance, sold for $100 million in January.

Graffiti, which also first appeared in the 1970’s, is still present though. It’s no longer the scourge of the subways that it once was, but it is still present, particularly outside of Manhattan. Mind you, it’s very much illegal, and the punishments are quite harsh: A felony charge awaits adults caught doing it, and stores are actually prohibited from displaying real cans of spray paint in their window, lest they tempt teenagers to steal them. Unlike in some European cities, there are no areas of the city where it is legal to do graffiti, so if you want to do it without breaking the law, you have to partner with a building owner.

But despite graffiti’s association with crime, it is very much a part of the cultural fabric of New York City, and in the right context, it can empower local communities and enliven streetscapes that are simply being scrubbed blank today.

I’m talking about this sort of thing:

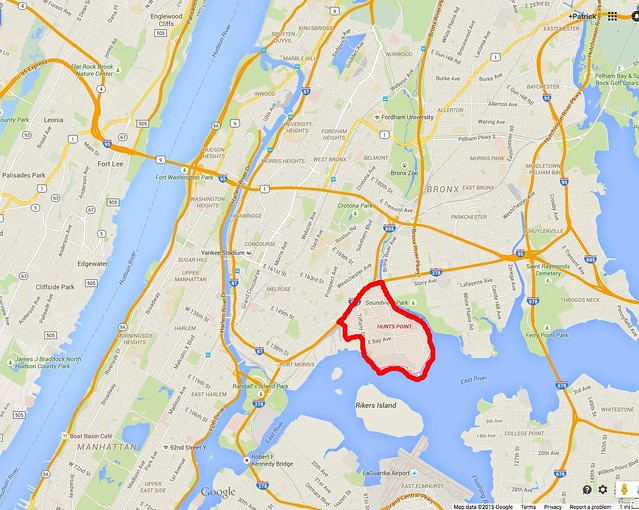

This is a mural in the central Brooklyn neighborhood of Gowanus that was done with the building owners’ permission. For my thesis, I visited six locations around the New York City metropolitan area to learn how these kinds of murals are created, and the effects they have on the area. Today I’m going to focus on one of those locations, Hunts’ Point in the Bronx.

The Bronx is the poorest of the five boroughs, or counties, in New York City, and Hunt’s Point is one of the poorest parts of the borough. But it’s also the site of amazing graffiti, thanks to the TATS Cru, a group of graffiti artists who have created a business out of graffiti. In Hunts Point, they do murals like this:

And this

And this

The TATS Cru’s work in the Bronx is relevant to a conference about Cultural and Creative Industries, because the group members are from the area, and rather than displace the poor, they use the tools of an art form that was invented on the streets, and is extremely democratic. One need only secure a wall and spray paint to bring color to the masses. And that’s what Hector Rodriguez, one of the founders of the TATs Cru, told me when I interviewed him. I quote:

“Not everyone in New York City really has the time to partake in the art culture that’s out there. The stuff that we’re putting out there in these neighborhoods, is the modern day Picassos, Goyas and Monets that bring art and color to other people’s lives. They don’t have any other color in their life, outside of what we’re painting out there.”

Just up the road from Hunt’s Point is another mural that the TATS Cru did that I’d like to share with you.

There are murals like this all over New York City, and they serve a very important function: They preserve local culture and tell residents that their community has value beyond mere real estate values. They are, in the words of Marxist scholar David Harvey, “Marks of Distinction,” which he says represent and I quote, “the collective symbolic capital that a city has accumulated through authenticity, uniqueness, and particular non-replicable qualities.”

Graffiti is a global art form today, but it was born on the streets of New York in the 1960’s and 70’s. It distinguishes New York from other places more than the One57 residential tower that I mentioned earlier, which are simply cogs in the transfer of capital from one global city to another.

I’ll take this over towers like that any day.

Because many New Yorkers still associate graffiti with life in 1975, when 1,645 people were murdered there, it’s easy to understand why city government is hesitant to partner with graffiti artists. For comparison, there were a record low 328 murders last year.

It’s an example of “symbolic interactionism” a theory which states that people interact with each other by interpreting or defining each other’s actions instead of merely reacting to each other's actions. They don’t hate graffiti because of what it is. They hate it because of what it represents, which is a loss of control over space.

New York City currently reclaims that space for building owners for free, by erasing, or “buffing” graffiti, under a program over seen by the Economic Development Corporation. This helps owners regain control of their space, but I would argue that because the city government does not also promote partnerships building owners with artists who might want to create graffiti murals, it is missing out on an opportunity to promote a homegrown creative industry.

Although graffiti murals are primarily found in gentrifying neighborhoods that are popular with artists, such as Bushwick in northern Brooklyn, they can also be found in “uncool” areas like Staten Island, Trenton, New Jersey, and Hunt’s Point. And industrial neighborhoods have always been ripe for murals; I couldn’t help but be amazed at the amount of art in Zorrozaurre.

Regardless of where they are, they have the power to make a junkyard in Hunts Point into an art gallery.

Regardless of where they are, they have the power to make a junkyard in Hunts Point into an art gallery.

In some cases, building owners hope that murals will help spur gentrification, but many simply desire a space that’s more aesthetically pleasing than graffiti tags. And while most would agree that a wall that’s been buffed clean is better than a wall that looks like this:

My task has been to show how graffiti murals are better than both. The partnerships that currently exist between owners and artists who create murals are significantly better both for them and members of the community, who I also spoke to during my site visits. In Brooklyn, a building owner compared murals to growing a garden in an alley, while a resident of Jersey City said to me, and I quote:

“Tagging is usually done out of vengeance. You know, you’re mad at someone, you’re mad at the person in the building and you just want to tag something, just to let them know that you was here, and you really don’t care if it’s painted over or if it’s clean, you know, when the bricks are clean. But when you do a mural like this, you’re really putting your heart into it. So it’s totally different.”

Finally, there’s the issue of authenticity. In 1939, Walter Benjamin wrote, and I quote, “the uniqueness of the work of art is identical to its embedded-ness in the context of tradition. This tradition itself is thoroughly alive and extremely changeable. What was equally evident to both was its uniqueness, its aura.”

Graffiti murals are derived from the tags that first appeared on the streets and subways of New York. Their aura is on the street, and it’s partly because of this authenticity that people from around the world flock to see the graffiti and street art of New York.

In conclusion, I am optimistic that the people in New York are beginning to understand the value of graffiti murals. The six owners I spoke to for my thesis are great examples of private property owners who prefer art over blank spaces, and there are two other groups that are leading the charge to beautify the city: The city’s department of transportation, and Groundswell, a non profit group.

If you’d like to learn more, my thesis is being published in August as a book; I’d be happy to share more info with you on how to buy a copy.

Thank you.